AS ABOVE, SO BELOW:

Barbara Boissevain and Charlotta Hauksdóttir

Chung 24 Gallery, San Francisco

July 22-Sept 13, 2025

“With rolling black sand beaches, mist-wreathed mountainscapes, cerulean glacier tongues and bubbling hot springs, Mother Nature has candidly outdone herself decorating this small Atlantic island.” An English writer described the wild beauty of Iceland, “ a cornucopia of natural splendor” so different from green and pleasant England, in gloriously romantic terms appropriate to touristic travel guides. To be sure, Iceland does a and-office business, so to speak attracting pilgrims in search of the unspoiled scenery, including fine-art photographers, and leaving behind some of the unfortunate by-products of commercial development—not just trash but also the commercial-consumption mentality relegating the experience of wildness to a kind of lifestyle trophy: see it now before the others spoil it. While Ireland has its preservationists, the small population iff islanders is by no means deep Green when it comes to consumption, ranking among the big spenders of global capitalism. In his 1948 novel, The Atomic Station, the novelist Halldor Laxness dramatized the perils of Cold War modernization, with his young heroine, Ugla, purportedly based on an early environmentalist, expostulating on the objectification and commercialization of the—for her, a spiritual descendant of the Norse pantheists of the pre-Christian era—sacred wilderness:

Who thought up the theory that Nature is a matter of sight alone? … Nature is in front of us, and behind us; Nature is under and over us, yes and in us, but most particularly it exists in time, always changing and always passing, never the same, and never in a rectangular frame.

As Above So Below presents two eminent Bay Area photographers—their monographs are available at the gallery— who are undoubtedly ethically in sync with Ugla (despite her dismissive opinion of rectangular art), if not aesthetically: the American-born Barbara Boissevain and the Icelander Charlotta Hauksdóttir. The phrase—in Latin, ut supra, ut infra—is used these days in legal documents to cite quotations elsewhere in the text, but it derives from earlier, pagan sources in medieval alchemical and mystical lore asserting that the earthly and heavenly worlds are united through sympathetic magic (esoterically prefiguringHegelian and Marxian dialectic). As it is in heaven, so it is on earth; the universal mirrors the personal; the external world reflects the internal world; the cosmos is reflected in the individual; and the macrocosm is reflected in the microcosm. The title could be also said to refer to the imagery and construction of the works: more on the double/Doppelganger aspect, ut infra.

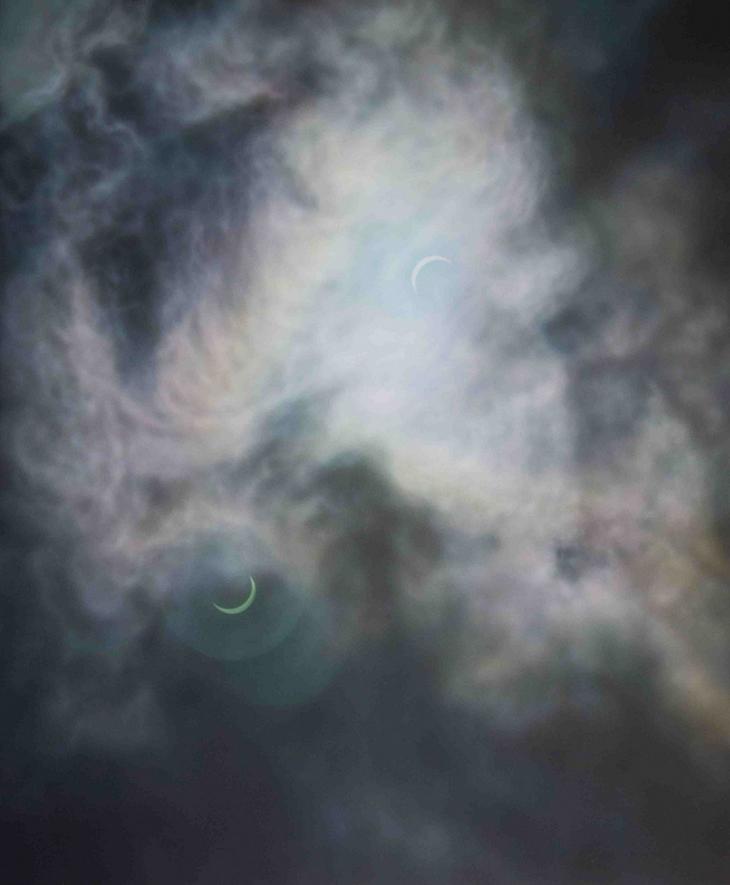

In 2015, Boissevain photographed Iceland’s stunning mountains, glaciers and icebergs, and years later returned to her images in her Endangered Ice series, mindful of the growing effects of global warming, and interested in moving beyond visual beauty to express her environmental concerns while not excluding eye appeal from her conceptual, subtly sociopolitical approach. Boissevain’s six new mixed-media pieces combine her earlier digital prints with watercolor and monoprint revived from from her grad-school painting years. The five photo hybrids from the 2024 Endangered Ice series depict blue icebergs shown in elevation, removed from the landscape ,and mounted on unpainted backgrounds like biological specimens. with their large submerged masses tapering into triangular roots, like jellyfish, mushrooms, thunderclouds dripping precipitation, or extracted teeth. The suggestive ambiguity of the forms contrasts well with the visual power of Boissevan’s rhythmic brushwork, creating heavy sculptural-looking masses that hover mysteriously, mid-air. Clouds also some to mind. The fifth piece, “Endangered Ice Shadow Installation,” from 2025, contains similar iceberg-clouds, but here, the painted shapes are mounted on plexiglass pieces cut to fit, and mounted on plexiglas dowels a few inches out from the wall upon which they cast shadows, suggesting islands or continents, seen from above, floating in a crystal clear sea.

Hauksdóttir takes a s different direction in her four 2D “photography collage” works, which depict rugged mountainscapes in a traditional

pictorial slice-of-life manner but subvert (or enrich) that style (which

Laxness’s Ugly might have disliked, as executed by postcard-scenic

painters, by scissors-cut excavations into the earth, seams or

sinkholes. Through these apertures in “Erosion XII” and “Erosion XIV”

(both 2024) we perceive a surprising subterranean layer of text aligned

with the surface geomorphology —an underworld of words describing the

past and future of the geology that “exists in time, always changing

and always passing, never the same,” though presented here within the

dreaded rectangular frame. In “resurgence IV” and “Resurgence XIV” (both

2024), Hauksdóttir imagines the land recovering, with new plant life

emerging below the surface, even reaching beyond the current topography

into the sky. A trio of “Reclamation” sculptures made between 2023 and

2025 and “Into Deep” (2025)—in too deep?—show the artist taking a more

conceptual approach, fabricating geometric shapes from branches on which

her photos are rolled that are sewn together, simulating indigenous

artifacts of some vanished tribe that possessed photographs and wished

to commemorate or magically contain, protect or regenerate the natural

world.

If culture has too often historically given nature short

shrift, following the reductive rationalism of toxic capitalism (and

all-too-human slash-and-burn human nature), there is no need to keep on

fatally fouling our nests. No one is coming to rescue us; we're not off

to some Martian billionaire bunker utopia to hatch a new race of moral

derelicts. Art is not politics, but it can be part of the solution, one

small epiphany after another.